BODWELL’S BAKER’S DOZEN 2024

From 2009 to 2019, I issued an annual list of the most memorable books I’d read each year. I did not issue lists in 2020, 2021, 2023. During that time, however, I did post more than 200 suggestions on social media for “SOCIAL DISTANCING READING,” a project that began Saturday, March 14, 2020 with A Bibliographic Checklist 1969-1979: Capra Press. It was, for us here in Maine, the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.

Why a “baker’s dozen” of books rather than the conventional “Top Ten” list? It’s simple: back in 2009 I couldn’t manage to cut three books I really admired from my list—or to be more precise, I didn’t want to cut three books just to fit some arbitrary constraint.

In addition, I immediately decided that even though most year-end roundups focus on titles published during the year the list was written, my lists would be less didactic and more of an authentic representation of a real reading life: We are both always behind, always discovering. Before 2016, for instance, I’d never read Penelope Fitzgerald’s perfect short novel The Bookshop. Even though the book was first published in 1978, I had to include it on my 2016 list. It was, after all, new to me.

Finally, my aim was never to synopsize or review the books on my list, as is often the norm for annual lists, but to contextualize the books within my life, to note how I’d come to read the book or why I’d been moved to include it on my list.

(PHOTO: The current author of Bodwell’s Baker’s Dozen relaxes on Bardsey Island off the coast of the Llyn Peninsula in northern Wales. The destination of pilgrimages since the sixth century and said to be the burial ground of 20,000 saints, the island was owned by the Bodwells from 1554 to 1722. It was on Bardsey that the first Bodwell’s Baker’s Dozen was discovered, etched into a piece of granite.)

A LITTLE DEVIL IN AMERICA: NOTES IN PRAISE OF BLACK PERFORMANCE

Hanif Abdurraqib

Hanif Abdurraqib leaps with confidence; his is a mind I’d follow anywhere. He can make the known fresh, too; his telling of Merry Clayton singing backup vocals on the Rolling Stones’ 1969 song “Gimme Shelter” is riveting.

In late July of 2024 I spent a long weekend at the 65th Newport Folk Festival accompanying Joan Baez through a series of readings and appearances; I edited Joan’s debut poetry collection, which had been published in April. After the festival, we hung around Newport for another day so Joan could appear in conversation with Abdurraqib at a sold-out book event hosted by Charter Books. He was brilliant, of course; Joan joked several times “Your questions are too smart for me!”

“History, both the arm holding down the drowning body and the voice claiming the water is holy.”

(Random House, 2001)

BOY IN A CHINA SHOP: LIFE, CLAY, AND EVERYTHING

Keith Brymer-Jones

My wife-to-be began watching The Great Pottery Throw Down without me during the pandemic. She was recommitting herself to her pottery practice and thought the show was too esoteric for me, a non-ceramicist. But one weekend, I walked into the living room and there was Keith Brymer Jones on screen, in tears, his voice wavering, telling an amateur potter their work was “Absolutely brilliant.” Who was this giant, tender man!? I was riveted.

Brymer-Jones’s memoir memoir reads like you’re sitting with the wonderful man over a pint in a pub and he’s charming you with stories. That he’s frequently touching on his Welsh heritage is gravy.

“There is a Welsh saying that goes . . . wait for it . . . ‘Ara bach a bob yn dipyn mae sdicio bys i din gwybedyn.’ This translates, and you’ll be pleased to read this, as, ‘You have to take it very slowly and bit by bit to get your finger up a fly’s arse.’” Charming! Clearly, it is a rather odd way of expressing that old adage that patience is a virtue, and beautifully illustrates what a singular, characterful folk the Welsh are.”

(Hodder & Stoughton, 2022)

A MONTH IN THE COUNTRY

J.L. Carr

In early October of 2024, my wife and I ended our nearly two month honeymoon with a couple of days in Wrexham, Wales. It was there that I finally picked up a copy of this masterpiece in miniature. Barely 100 pages, A Month in the Country is narrated by Tom Birkin, an old man at the end of his life who looks back on the summer of 1920 when he was a young, broke and broken WWI veteran hired to restore a medieval mural in a rural Yorkshire church. He camps rough in the belfry, befriends a fellow veteran and archaeologist living in a tent in the churchyard, finds in his attraction to the reverend’s beautiful wife that he might yet move past his imploded marriage, and gingerly learns to accept the kindnesses of the villagers.

“If I’d stayed there, would I always have been happy? No, I suppose not. People move away, grow older, die, and the bright belief that there will be another marvelous thing around each corner fades. It is now or never; we must snatch at happiness as it flies.”

(Harvester Press, 1980)

GHOST DOGS: ON KILLERS AND KIN

Andre Dubus III

Dubus’s ability to ask difficult questions of himself seems without end, as does his acceptance that some questions are without answers. His ability to own his mistakes is humbling. The title essay is a stunner. “The Golden Zone," about hunting a hit man in Mexico, is riveting. "If I Owned a Gun” is worth the cost of the book. Of course, I love every moment of “Carver and Dubus, New York City, 1988” about the one time his father and Raymond Carver met and their mutual affection for one another. But I think the essays “Pappy” (about Dubus’s maternal grandfather) and “Relapse” (about the siren song of physical violence) best encapsulate a thread that runs through much of the book and most captured my attention: The failure to live up to our own expectations of ourselves is a human condition I accept, embrace, and value.

"What became clear to me ... is how much of the layered texture of our lives is shared by others. And how the reading of one person's story can bring us more fully back to our own."

(W.W. Norton, 2024)

OFFSHORE

Penelope Fitzgerald

This was a re-read, but it’s so damn good that I’m including it: Fitzgerald published her first novel (The Golden Child) in 1977 at the age of 61. Her second novel, The Bookshop, was published in 1978 and shortlisted for the Booker Prize. Offshore was Fitzgerald’s third novel. Published in 1979, it won the Booker Prize that year. At 132 pages (in its first edition printing), Offshore remains the shortest novel to ever win the Booker. This strangely engrossing novel is set amongst the odd menagerie of houseboat residents permanently moored at the Battersea Reach on London’s Thames River. It focuses on single-mom Nenna and her precocious daughters, Martha (12) and Tilda (6), who live aboard Grace. Offshore brims with Fitzgerald’s signature mercurial technique and is a case study of how to deploy humor in a serious work.

“If Richard was not at home with words, still less was he at home with questions of a personal nature. He might as well capsize the dinghy and be done with it. But he waited, watching her gravely.”

(Collins, 1979)

GREENE ON CAPRI

Shirley Hazzard

When I began editing Michael Mewshaw’s charming memoir My Man in Antibes: Getting to Know Graham Greene a couple of years ago, I knew very little about Greene. I’d never read one of his novels. I think this—combined with my generally high level of curiosity—made me a good editor for that book: I wasn’t distracted by Greene’s talents with language on the page, nor his talent for mythmaking off. I’ve still never read a Graham Greene novel, but I found Shirley Hazzard’s economical and elegiac memoir of her old friend oddly captivating.

“On a December morning of the late 1960s, I was sitting by the windows of the Gran Caffè in the piazzetta of Capri, doing the crossword in The Times. The weather was wet, as it had been for days, and the looming rock face of the Monte Solaro dark with rain. High seas, and some consequent suspension of the Naples ferry, had interrupted deliveries from the mainland; and the newspaper freshly arrived from London was several days old. In the café, the few other tables were unoccupied. An occasional waterlogged Caprese—workman or shopkeeper—came to take coffee at the counter. There was steam from wet wool and espresso; a clink and clatter of small cups and spoons; an exchange of words in dialect. It was near noon.

Two tall figures under umbrellas appeared in the empty square and loped across to the café: a pair of Englishmen wearing raincoats, and one—the elder—with a black beret. The man with the beret was Graham Greene.”

(FSG, 2000)

TRAIN DREAMS

Denis Johnson

In just over 100 pages this brilliantly paced novella traces in leaps and bounds the life of Robert Grainier, an orphan shipped by train in 1893 into the woods of the Idaho panhandle. The writing is spare and confident; one might believe it’s a work of nonfiction. Johnson’s writing is so calm that it is, at times, unsettling. But Johnson’s great “twist” to the genre of the hardscrabble American West in the early twentieth-century is that even as Grainier experiences periods of truly horrible hardships and suffering, his story remains somehow tender.

“The wolves and coyotes howled without letup all night, sounding in the hundreds, more than Grainier had ever heard, and maybe other creatures too, owls, eagles—what, exactly, he couldn’t guess—surely every single animal with a voice along the peaks and ridges looking down on the Moyea River, as if nothing could ease any of God’s beasts. Grainier didn’t dare to sleep, feeling it all to be some sort of vast pronouncement, maybe the alarms of the end of the world.”

(FSG, 2011)

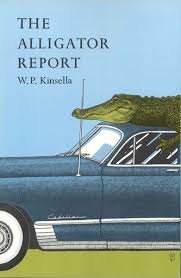

THE ALLIGATOR REPORT

W.P. Kinsella

Canadian author W.P. Kinsella is best known for his novel Shoeless Joe, which was adapted into the film Field of Dreams. Published in 1985 (three years after Shoeless Joe), The Alligator Report packs 26 stories into 134 pages. It’s an unabashed homage to the stories of Richard Brautigan—in his introduction, Kinsella even calls his stories “Brautigans” and there’s a story titled “The Resurrection of Trout Fishing in America Shorty.” As in so much early Brautigan, the weirdness is tinged with sweetness.

“Once, when I still believed in Chevrolet, apple pie, and the principle of pre-measured douche, I decided to sell life insurance. It looked like a quick way to make some money.”

(Coffee House Press, 1985)

GRANITE HARBOR

Peter Nichols

I discovered Peter Nichols via his rollicking literary novel The Rocks. Then I devoured his stunning memoir Sea Change: Alone Across the Atlantic in a Wooden Boat. If I’d read his debut thriller Granite Harbor any faster, I’d have torn the pages. The quality of Nichols’s writing and storytelling elevates this far beyond any preconceptions one might have about the gruesome tale of a serial killer on a spree in a quiet Maine town. If there was already a sequel featuring English-born novelist-turned-smalltown-detective Alex Brangwen, I’d have picked it up the day I finished Granite Harbor—which is, like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, ultimately about the helplessness of being a parent.

"I hoped that if there were any evil people out there, I would find them before they found my little boy."

(Celadon Books, 2024)

OH, WILLIAM!

Elizabeth Strout

Oh, Elizabeth! On nearly every page of Elizabeth Strout’s Oh, William!, I found myself wondering about our author-narrator Lucy Barton’s novels. How much are they like or not like Lucy talking to us about her life? I wanted to know, even though Lucy rarely lives her life with the authority she so admires in others, does she write with authority?

“Grief is such a—oh, it is such a solitary thing; this is the terror of it, I think. It is like sliding down the outside of a really long glass building while nobody sees you.”

*I also read Strout’s Lucy by the Sea this year and was delighted by the moments when get to observe Lucy trying to write a short story in her new makeshift studio during the height of the COVID pandemic.

(Random House, 2021)

THE NIGHT ALWAYS COMES

Willy Vlautin

“Gritty” does not even begin to describe Willy Vlautin’s The Night Always Comes. There are moments when you wince and wonder how many horrific incidents young Lynette must suffer as she attempts over the course of two days and nights to beg, borrow, and steal enough money to buy the house she rents with her mother and brother. This book is Brutal, with a capital B. But Vlautin is also one of the most empathetic, least patronizing writers I can think of. It’s quite a feat to make a story of class, gentrification, and mental health an absolute page-turner.

“There is always that dream of escape, but there is no place to escape to, you just run into yourself.”

*I also read Vlautin’s The Horse this year, which must have the best compilation of fictional country and western song titles ever written.

(Harper, 2021)

THE HAPPIEST MAN IN THE WORLD: AN ACCOUNT OF THE LIFE OF POPPA NEUTRINO

Alec Wilkinson

Joseph Mitchell made literary magic out of Greenwich Village eccentric Joe Gould. But in Poppa Neutrino (born David Pearlman), the anti-hero at the heart of The Happiest Man in the World, Wilkinson has much more material to work with. Vagabond, dreamer, sea raft captain, football play philosopher, Neutrino is endlessly, gaspingly interesting (as are the cast of characters he mixes with). The book sings because Wilkinson is incredible with dialogue and pacing, and the sort of stylist whose sentences constantly surprise and delight me. But it’s Wilkinson’s earnestness and big-heartedness that make me curious about reading anything he’s curious about.

“He was wearing a dark shirt and a pair of dark nylon shorts over his dark trousers. I said I had never seen that look before. He said his zipper was broken. Then he asked if I thought it looked strange, and I said it looked fine and, oddly, on him, it did.”

*I also read Wilkinson’s The Protest Singer: An Intimate Portrait of Pete Seeger this year, which is a must-read for anyone thought Ed Norton as Pete Seeger was one of the best parts of the movie A Complete Unknown.

(Random House, 2007)

THIS IS HAPPINESS

Niall Williams

In Niall Williams’s This Is Happiness it is the summer of 1958 in the (fictional) rural Irish hamlet of Faha, a “forgotten elsewhere,” and electricity is finally coming to the village. The novel’s heart (and narrator) is Noel Crowe, known as Noe, who has dropped out of the seminary after his mother’s death and come to stay in Faha with his grandparents, loving called Doady and Ganga. But it is the novel’s framing device that makes it so rich and satisfying: it is told by Noe when he is a 78-year-old man looking back at the moments of dramatic change in his youth. This Is Happiness is a stunningly Irish novel: lyrical, unrushed, winking, melancholic, teeming with detours and digressions, brimming with sentences I read and re-read and underlined.

“As though an infinite store had been discovered, more and more stars kept appearing. The sky grew immense. Although you couldn’t see it, you could smell the sea.”

(Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019)

BONUS READING!

My Favorite Welsh Poetry

Girls, Etc.

Rhian Elizabeth

(Broken Sleep Books, 2024)

Sharp and funny, self-effacing as it mines, amongst other things, motherhood and queerness, what’s not to like about Rhian Elizabeth’s work? The work bristles, with anger, sure, but love, too, and grief and humor, always humor, because this poetry is like a late-night conversation with your best and most frank friend.

My Favorite Trip Back to My Teens

The Yellow-Lighted Bookshop: A Memoir, A History

Lewis Buzbee

(Graywolf, 2006)

Lord, this book made me miss the pre-internet days of book shopping. Back then you could set out with a divining rod and not only find a book but discover books: you came upon trickling streams and swift rivers you didn’t expect, even the occasional breathtaking waterfall. Today, it often feels like we’re trying to drink from a firehose. Buzbee began as a teenaged bookshop clerk, became a book sales rep, then an author. He’s a charming guide through not only his own history with books but through the history of all books.

“When I walk into a bookstore, any bookstore, first thing in the morning, I’m flooded with a sense of hushed excitement.”

Truly Stellar Story Collections

Last Car Over the Sagamore Bridge

Peter Orner

The Disappeared

Andrew Porter

Great Short

It’s tricky to keep track of the loads of great short stories and essays I read in magazines and literary journals over any given year, but I found unforgettable this one unforgettable:

“Projections of Life”

David Owen

(The American Scholar, July 2023)

*Owen writing about his grandfather: “Like other men of his generation, he pulled his pants several inches above his navel and used his stomach as a ledge to hang them from. (The father of a friend of mine once described such pants as “a little tight under the arms.”) Pants in those days weren’t cut the way pants are today. Because men wore them so high, the zippers had to be almost as long as jacket zippers, and the pockets were big enough to carry groceries.”

And, Finally, A Word from The Missus

This strange annual project began one afternoon in 2009 while I was waiting for my then-girlfriend to finish up some work at her desk so we could go goof off. This past June, that then-girlfriend became my now-wife. Sometimes our reading and tastes overlap, sometimes they don’t; she said “Meh…” to Denis Johnson, but loves Willy Vlautin. Oftentimes my wife is reading books I haven’t read. Here are a few books Mrs. Bodwell loved in 2024:

The Adversary

Michael Crummey

Bad River Road: Poems

Debra Nystrom

On the Tobacco Coast

Christopher Tilghman